As You Are.

Making Sense of Making Sense.

Prologue

Before we get into this, I want to acknowledge again that this is not my day job. Substack has become something of an intellectual sandbox where I play with the ideas that pollute my days and nights.

This particular topic of cognitive theory and more specifically that of predictive processing consumed me for years, is going to be a central theme of this page and a cornerstone of my upcoming book. As I think it should be fundamental in our practice of athletic training, skill acquisiton and injury rehabilitation.

With that being said, I want to tip my hat to the people who have paved the way for my understanding of this type of thinking.

David Marr, and his book Vision, was the first off-ramp I took from the conventional, unspoken understanding of perception. His pioneering work in computational neuroscience was the thin edge of the wedge that began to crack my mind open.

Anil Seth, Shamil Chandaria, and Sam Harris. Not only leading the way in communicating the complexities of this model, but also highlighting the practical application and endless utility that comes with this philosophical shift.

And lastly, the OGs:

Hermann von Helmholtz (past), whose theory of unconscious inference set the stage for this entire field of study.

Karl Friston (present), whose Free Energy Principle stands as the theoretical and mathematical backbone to the entire field of study.

Introduction

In my inaugural Substack article Sports Science, Saccades, and the True Nature of Reality I talked about the first glitch in my perceptual matrix. A short tale about how studying concussions in undergrad left me batting at the frayed ends of reality as I knew it.

Since then, a number of readers have reached out, sharing their own stories of analogous events—moments that brought them into contact with consciousness, religion, or neuroscience.

For some people, the vessel was a near-death experience. Others, a religious miracle. And for some, it was absolutely heroic doses of acid, shrooms, or psychedelic adjacents.

But regardless of how different the scenarios may have been, they’ve all independently reported an “aha!” moment . As if something or someone came up and put its hand on the glass of reality they’d been unwittingly looking through.

Their perception has been forever changed…

But this begs the question:

What do we mean by perception?

Perception is a concept that is as nebulous and ill-defined as the idea of consciousness or god itself.

For as many people as there are in the world, there likely exists the same number of definitions of the word perception.

You are probably conjuring up your own working definition of the term as we speak.

But if you don’t have one, let me offer you a one-size-fits-all outline of the way most people think perception works ,and you can use that to try these two prevailing theories on for size.

The Passive Illusion

Most people (including a prior version of myself) view perception as the passive interpretation of the outside world, playing out in front of them on the IMAX screen of their retinas, accompanied by the Dolby Digital surround sound of their ears, while the accompanying cast of senses taste, touch, and smell round out their avatar’s immersive experience of the world.

As if they’re someone, a small caricature of themselves, sitting in a La-Z-Boy behind their eyes, enjoying the film of their life as some sort of second-hand experience.

As if the outside world were imprinting its sensory data on our brain.

Makes sense, right?

To quote a great friend of mine, Kyle Rogers:

“It makes sense… if you don’t think about it.”

Well, people have thought about it.

Really smart people. For a long time.

And what they’ve come up with… well, it MAKES SENSE.

Literally.

The Generative Model

When we examine the neurological correlates of perception, we can start to dispense with the passive La-Z-Boy version of the outside world impressing itself on our brain.

And we quickly realize that the brain itself is in the driver’s seat of generating our perceptions. Taking the sense data, prior experiences and projections of our future expectations to actively create our perception of the world in real time.

Where the passive model sees perception as a direct result of our sense data, merely taking in the outside world as it is.

This generative model has our perception as a end result of a multilayered process where raw sensory data, prior experiences and future predictions are calculated and weighed against one another to generate our experience in real time.

This subtle but powerful shift is at the heart of a philosophical revolution that is turning the neuroscience world upside down, and not a moment too soon.

Since René Descartes, we’ve worked from the philosophical presumption that sense data was something of a mainline into our perception of the outside world as it is.

But advances in cognitive theory, specifically in the study of predictive processing, have shifted this philosophy 180 degrees. And this shift has already begun to bear fruit in how our science overlays with our philosophy.

So, What Is Predictive Processing?

Predictive processing is a theory of cognition that postulates that we don’t (and can’t) perceive the world as it is.

Rather, what we perceive is being generated by a top-down inferential loop, a loop that is merely constrained, not defined, by incoming sense data.

In other words, the brain is not passively waiting for the world to arrive.

It’s already making guesses.

At every level of the brain’s sensory hierarchy, predictions are being cast forward about what you’re about to see, feel, hear, taste and ultimately perceive.

When the actual sensory input arrives, it's not taken as gospel.

It’s compared against the prediction.

And only the difference, what neuroscientists call prediction error, is used to revise the model.

In simple terms our brain is utilizing the aggregate of sense data and generating its perception of the world. Our perception ultimately governs our sensation.

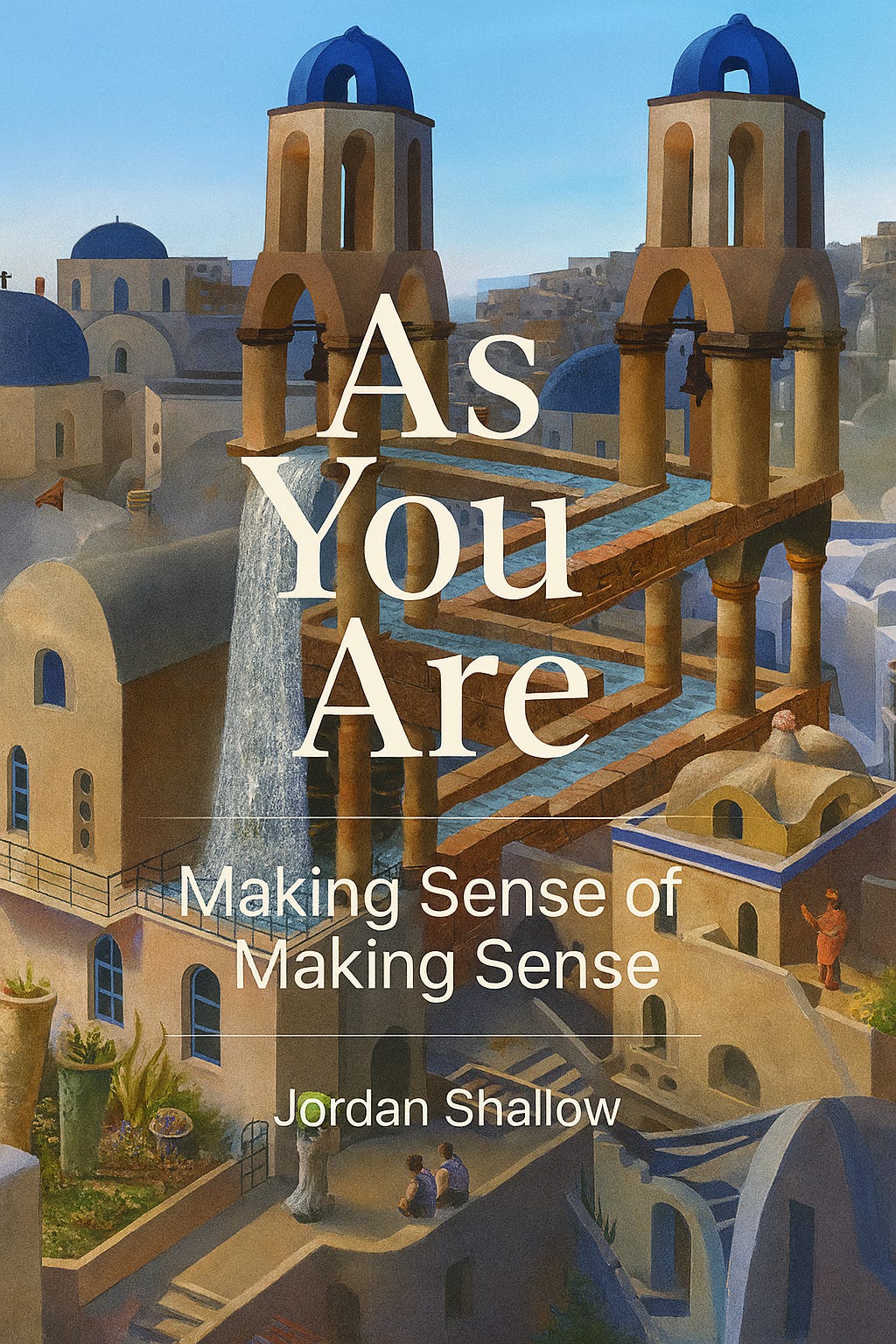

This can be seen in something as novel as trying to perceiving the beginning of Escher's Waterfall (image above) or something as profound as understanding pain.

When you realize that your brain is creating your perceptual experience only then can you start to harness this information to make real changes.

Perception as Inference

Perception, then, is not the world revealing itself to us.

It is the brain’s best guess.

It’s our brain making sense.

As Karl Friston and Anil Seth famously coined, our perception is something of a:

“Controlled hallucination.”

This flips the logic of classical neuroscience on its head.

Where Descartes once said:

Cogito ergo sum

“I think, therefore I am.”

Predictive processing offers something even more radical:

I predict, therefore I perceive.

Why It Matters

This explains not only why we often see what we expect to see,

but also why illusions work,

why pain persists,

and why reality can feel so stubbornly personal.

Because it is.

Your experience of the world isn’t streaming in from the outside.

It’s being generated and projected from the inside out, and only updated when the world pushes back hard enough to force change.

(We’ll see Baye’s enter this conversation here in the coming weeks)

Which makes perception not just a passive window onto the world...

But a mirror into the current, past, and potential future states of your brain.

A mirror that reflects back not things as they are, but as you are.

Closing Thoughts

Now look, it's easy for me to end on a poetic metaphor.

But I want to ground this theory in reality, for those of you following me over from my day job as a talking head in the space of functional anatomy, injury rehabilitation, and biomechanics, buckle up, because this thought experiment does way more than just blow your mind.

It will lead you down a path of thinking that will drastically change the way you practice, and as a byproduct, drastically change the results you get.

Stay tuned.

Jordan

I could feel my saccades reading this one

Great content!

Looking forward for upcoming articles.